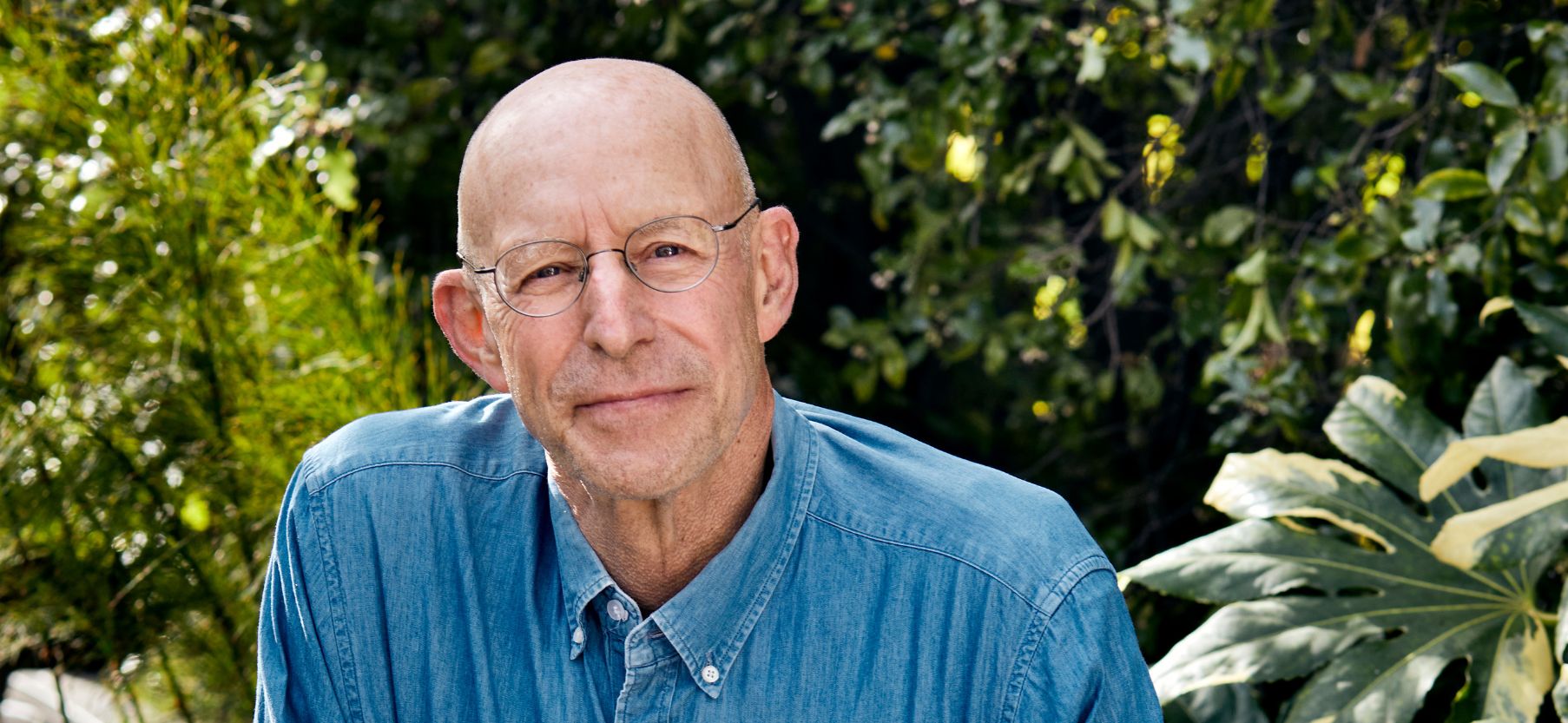

When Michael Pollan’s 2018 book How To Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence was published, it became a figurehead for the then-nascent psychedelic renaissance. A botanist and food writer whose books and work in the New Yorker and Harper’s had become synonymous with ethical eating, Pollan’s book was seen as adding a sheen of credibility to the world of pills and potions, and as an unexpected detour from his usual focus on gardening, cooking, and other urbane forms of leisure. As one NYT reviewer noted, Pollan remained concerned with plants, but “we aren’t talking about arugula.”

Pollan’s latest book, This Is Your Mind On Plants, offers a corrective to anyone who thought interest in psychedelics didn’t dovetail neatly with his botanist roots. In it, he seeks to answer a question that has been at the heart of the ways we discuss psychedelics: what is the difference between a drug and a plant?

Plant or Foe?

The reason this question is so hard to answer, according to Pollan, has less to do with differences between plants and drugs and more to do with how shaky those terms truly are. Defining what constitutes a “drug” is, in his view, a fool’s errand:

Is chicken soup a drug? What about sugar? Artificial sweeteners? Chamomile tea? How about a placebo? If we define a drug simply as a substance we ingest that changes us in some way, whether in body or in mind (or both), then all those substances surely qualify.

Rather than attempting to pin the definition of a drug to a stable category ( like an animal, plant, or mineral, for instance) Pollan argues that drugs are more of a social category, constantly shifting and evolving with the cultural context in which they’re used. He points out that indigenous communities from whom much of our knowledge about psychedelics originates made no attempt to separate these powerful substances from their status as plants. For Andean curanderos who use psilocybin-containing mushrooms in their healing practices, or members of the Native American Church whose religious ceremonies incorporate peyote, focusing on the power these substances have while still being wholly tired to the Earth doesn’t obscure their risks or promote irresponsibility, it enlarges our understanding of how humans relate to nature.

Three Plants and Three Drugs

Much like how How To Change Your Mind focused on a quartet of classical psychedelics, in This Is Your Mind On Plants he chooses three substances to interrogate the drug/plant binary: opium, caffeine, and mescaline (the psychoactive chemical in peyote). It is an unlikely trio at first glass, but Pollan’s personal history with each weaves them together into a kind of botanical biography.

Pollan’s experiences with opium stem from a previously published article written for Harper’s in which he attempted to cultivate opium by growing poppies in his home garden, and the ensuing legal drama that resulted in the excision on large portions of his essay. Pollan compares the arbitrariness with which a harmless decorative flower could become an illicit drug with the byzantine and contradictory logic of America’s War on Drugs. Here Pollan gives us the unredacted full text and points out the irony of opium’s status as an illicit drug while also forming the chemical foundation of OxyTocin, the prescription painkiller at the heart of America’s opioid crisis.

But what is true of the opium poppy is true for all the medicines that plants have given us: they are both allies and poisons at once, which means it’s up to us to devise a healthy relationship with them.

Michael Pollan’s adventures with caffeine are more personal, as he details his attempts to write this section of his book without his daily regime of coffee and green tea. Extracts from his journal describe a man with a bad cases of jonesing:

“I feel like an unsharpened pencil,” I wrote. “Things on the periphery intrude, and won’t be ignored. I can’t focus for more than a minute. What I miss is nothing resembling a state of intoxication or euphoria, just the simple gift of my normal everyday consciousness. Is this my new baseline? God, I hope not.”

Painfully relatable, Pollan consoles himself by looking at the plants from which caffeine is extracted, why it’s produced in the first place (turns out it’s lethally toxic to the insects who pester these plants) and the convenient slights of public opinion that keep us from thinking of our morning cup of coffee as a drug, despite the fact that it very clearly is.

Pollan’s chapter of mescaline is the most knotty and perhaps most intriguing. The ritual use of peyote in religious ceremonies has been a part of traditional cultures across North and Mesoamerica for centuries, and was the subject of Aldoux Huxley’s seminal 1954 book Doors of Perception. Today, members of the Native American Church, a patchwork religion that incorporates both indigenous tradition and Christian theology, have the legal right to use the plant as a part of their worship. As a result, illicit peyote has become hard to find and many would-be trippers have been forced to either look to other species of psychoactive cactus or, in some cases, turn to less than reputable “churches” that allow non-tribal members.

The psychedelic renaissance has put peyote-using members of the Native American Church in a bind: on the one hand the increasing acceptance of using psychedelics to access spirituality has reinforced their religious rights. On the other, increased demand for peyote by secular seekers threatens to expose the small legal shelter they’ve built for themselves, as well as overtaxing the supply of the slow growing cacti in which mescaline is found.

This puts the eating of peyote by white people in a long line of nonmetaphorical takings from Native Americans. I was beginning to see that, for someone like me, the act of not ingesting peyote may be the more important one.

This Is Your Mind on Michael Pollan

It’s clear that Michael Pollan has no intention of seeing his latest book become a tentpole in the psychedelic revolution, as was the case with How to Change Your Mind. This Is Your Mind On Plants makes for more discursive, percolating reading, and readers will come away less imbued with new knowledge than left questioning what they thought they already knew.