Dementia is not a specific disease, but instead the term collectively describes a range of symptoms caused by a variety of brain injuries and disorders. While Alzhiemer’s causes around 60-70% of dementia cases, other causes include strokes, alcohol abuse or repeated head injuries. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a condition caused by head injuries, which may develop into dementia as symptoms worsen.

While CTE commonly affects players of contact sports, military personnel and victims of domestic violence, the condition is difficult to diagnose reliably in living people as a post-mortem autopsy is currently the only way to confirm it conclusively. Common symptoms of CTE include cognitive, mood and behavioural impairments, which may often overlap with a diagnosis of other dementia-causing illnesses such as Alzhiemer’s.

In cases where CTE is suspected, current treatment regimes follow those for early-stage dementia more generally, which includes physical and cognitive therapies aiming to support the patient through their condition. Currently there are no FDA-approved medications designed specifically to treat CTE, but certain drugs are used off-label to treat different symptoms on a case-by-case basis. Such drugs include those designed to treat symptoms caused by other dementia-linked diseases such as Alzhiemer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as those used to treat depression and anxiety more generally. While drug treatments may reduce CTE symptoms, they may also come with a range of potential side effects which may worsen symptoms of brain injuries in other areas.

Psilocybin Treatment – Beyond Depression And Anxiety

At present, clinical research into psilocybin-based mental health treatments is best developed for depression, with studies on anxiety following closely behind. However, in recent years, scientists studying a range of conditions have looked to psilocybin as a potentially novel treatment, due to the ability of the substance to increase signal connectivity between different regions of the brain.

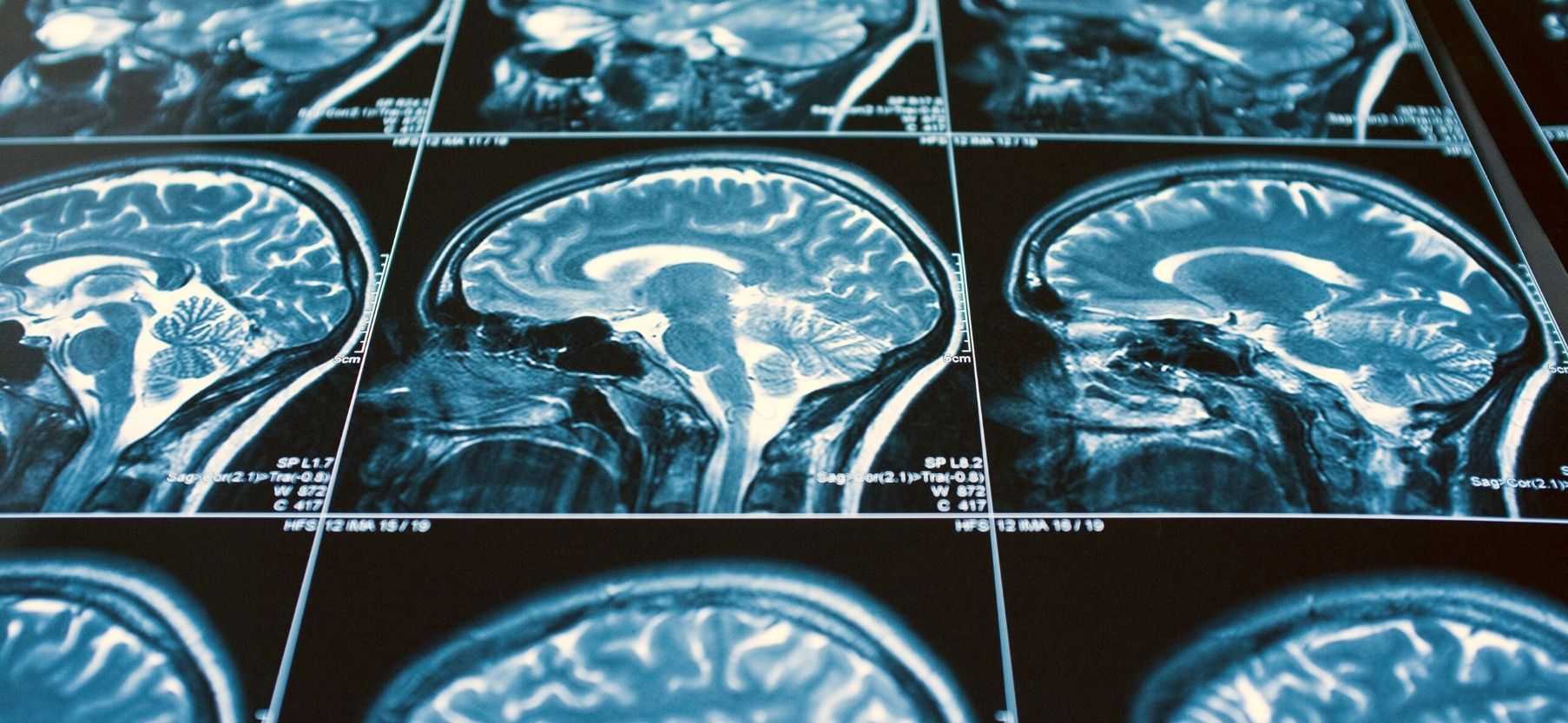

Understanding how psilocybin affects humans relies on non-surgical imaging techniques to record brain activity while under the influence. Early studies in 2011 found that psilocybin reduced blood flow to regions of the brain responsible for reducing signals between brain areas, effectively opening up new neural pathways. Years later, another study found that the brains of psilocybin-dosed subjects showed increased connections between regions, compared to an undosed control group.

While non-invasive scans are used in human psilocybin studies, changes in physical brain structure have been studied in animals. Studies of pigs dosed with psilocybin for brain injuries have shown an increase in proteins associated with nerve generation, and a study in rats was able to visualise the increase in points of contact between nerve cells, which persisted for at least one month after a dose.

In the case of people suffering from depression and anxiety, scientists believe that their maladaptive brain signals travel down rigid and fixed neural pathways, which become more entrenched as symptoms persist. Add to this the therapeutic application of psilocybin, and these same signals may be routed across new areas of the brain, bypassing old pathways and relieving symptoms – an effect that persists long after treatment for brain injuries has ended.

When it comes to dementia causing illnesses like Alzhiemer’s, Parkinson’s and CTE, some scientists theorise that psilocybin could induce a similar rerouting of brain signals, though in these cases allowing the sufferer’s brain to compensate by creating new signal pathways around areas which may be damaged.

Getting The Dosage Right

The therapeutic importance of a fully hallucinatory experience in patients receiving psychedelic treatment for brain injuries is something that is still up for debate. Some researchers claim that the relationship between a psychedelic experience and improved symptoms of depression may merely be coincidental, whereas others claim that experiencing the altered mental state associated with higher doses of psychedelics is crucial to maximising their therapeutic value.

The effect of low doses of psychedelics in humans is less understood. In some animal studies, psilocybin’s antidepressant-like effects have been noted at doses suspected to not be hallucinogenic. Although there is growing research into the microdosing movement, legal restrictions and difficulties in verifying dosages means that such research lacks the scientific rigour of clinically controlled trials with higher doses for brain injuries.

Nevertheless, understanding the effects of low doses of psilocybin and other psychedelics offers us a brave new world of research. This has led to some scientists calling for more attention to be paid to low-dose psychedelic trials, specifically in the case of dementia sufferers. In the case of CTE, prevention should certainly be prioritised over the cure, but insights gained from new studies into Alzhiemer’s, Parkinson’s and other dementia-causing illnesses may show promising results for treatment of brain injuries with psychedelics in the future.